Is there a fair price for a stock?

For most people, the stock market looks like a chaotic gambling arena where numbers flash red and green based on nothing more than luck or “vibes.” You see a stock trading at $150 today, and tomorrow it’s at $142. Does that mean the company is actually worth less today than it was yesterday?

The answer lies in one of the most important concepts in all of finance: Intrinsic Value. Legendary investor Benjamin Graham, the mentor of Warren Buffett, famously said, “Price is what you pay; value is what you get.” Understanding the difference between the price on your screen and the actual “fair price” of the business is the secret to long-term wealth.

In this deep dive, we will explore the science and art of stock valuation. We will look at how the pros determine what a company is “actually” worth and how you can use these techniques to avoid buying at the peak of a bubble.

Intrinsic Value vs. Market Price: Understanding the “Mr. Market” Analogy

To understand if a fair price exists, we must first accept that the stock market is often irrational. Benjamin Graham created the story of Mr. Market to explain this.

Imagine you own a small piece of a business. Every day, a man named Mr. Market comes to your door and offers to either buy your share or sell you his at a specific price. Some days, Mr. Market is incredibly happy and optimistic; he offers you a very high price. Other days, he is depressed and fearful; he offers you a very low price.

Does the business change that much every day? No. Mr. Market’s prices are driven by emotion, but the company’s “fair price” is driven by economics. Your job as an investor is to wait for Mr. Market to get depressed so you can buy from him at a discount, and wait for him to get euphoric so you can sell to him at a premium.

The Definition of Intrinsic Value

Intrinsic value is the “true” worth of a company based on its assets, earnings, and future growth potential, independent of its current stock price. If the intrinsic value is higher than the market price, the stock is undervalued. If it is lower, the stock is overvalued.

Top Stock Valuation Methods Used by Wall Street Pros to Find Undervalued Assets

How do we actually calculate this “fair price”? There isn’t just one way. Analysts use several “models” to triangulate a company’s worth.

1. The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Model

This is widely considered the “gold standard” of valuation. The theory is that a company is worth exactly the sum of all the cash it will ever generate in the future, brought back to today’s dollars.

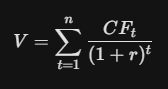

To do this, we use the Time Value of Money. A dollar today is worth more than a dollar ten years from now because you could invest the dollar today and earn interest. The formula for the present value of future cash flows looks like this:

Where:

-

V = Intrinsic Value

-

CFt = Cash flow in a specific year

-

r = Discount rate (the return you expect to earn)

-

t = The time period

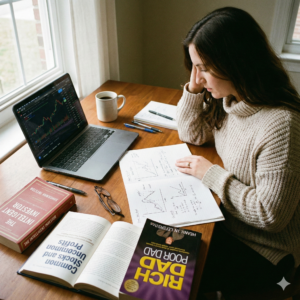

2. The Price-to-Earnings (P/E) Ratio

The P/E ratio is the most common “relative” valuation tool. it tells you how much investors are willing to pay for every $1 of a company’s profit.

If the average P/E for the tech industry is $25 and a great tech company is trading at a P/E of $15, it might be undervalued. However, you must be careful—sometimes a low P/E means the market expects the company’s profits to shrink.

3. Price-to-Book (P/B) Ratio

This method looks at the “tangible” value of a company—its buildings, equipment, and cash—minus its debts. This is called the Book Value. If a stock is trading below its book value (a P/B ratio of less than $1.0), you are essentially buying the company for less than its liquidation value. This is a classic “Value Investing” signal.

Why the “Fair Price” is Always Moving: The Impact of Interest Rates

One of the biggest misconceptions for beginners is that a fair price is a static number. In reality, the fair price of a stock is highly sensitive to the Macroeconomic Environment, specifically interest rates set by the Federal Reserve.

The “Gravity” of Interest Rates

Think of interest rates as gravity for stock prices.

-

When rates are low: Bonds and savings accounts pay almost nothing. Investors are forced into the stock market to get a return, which pushes “fair prices” higher.

-

When rates are high: You can get a safe 5% or 6% return from a government bond. Suddenly, a “risky” stock needs to offer a much higher return to be worth the risk. This lowers the “fair price” of the stock.

This is why, when the Fed announces an interest rate hike, almost every stock price drops instantly. The “math” of their value has literally changed.

The Role of Growth: Why Some “Expensive” Stocks Are Actually Cheap

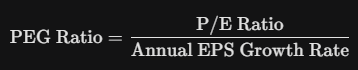

You might look at a company like Amazon or Nvidia and see a massive P/E ratio of $60 or $100 and think, “That’s not a fair price! It’s way too expensive!” But that is where the PEG Ratio comes in.

The PEG Ratio (Price/Earnings to Growth)

The PEG ratio factors in how fast the company is growing.

A company with a P/E of $40 that is growing at 40% per year (PEG = $1.0) is actually “cheaper” than a company with a P/E of $10 that isn’t growing at all (PEG = Undefined/High). When a company is growing rapidly, its “fair price” today includes the expectation of massive profits tomorrow.

Comparative Valuation: Using Peer Groups to Spot Discrepancies

No company exists in a vacuum. To find a fair price, you must compare a company to its “Peer Group.”

| Metric | Company A (Target) | Company B (Competitor) | Company C (Competitor) |

| P/E Ratio | 18 | 24 | 22 |

| Profit Margin | 15% | 12\% | 11% |

| Revenue Growth | 10% | 8\% | 7% |

| Dividend Yield | 2.5% | 1.5\% | 1.2% |

In this table, Company A looks like a bargain. It has a lower P/E ratio than its competitors despite having better margins and higher growth. This suggests that the “fair price” for Company A should likely be higher than its current market price.

The “Margin of Safety”: The Most Important Words in Investing

Even with the best math and the most advanced software, humans make mistakes. You might overestimate a company’s growth or underestimate its competition. This is why you must always use a Margin of Safety.

The Margin of Safety is the difference between your calculated intrinsic value and the price you pay.

Example: If you calculate the fair price of a stock to be $100, you don’t buy it at $100. You buy it at $70. That $30 gap is your “cushion.” If you were slightly wrong in your calculations, you still won’t lose money. If you were right, your gains will be even larger.

Qualitative Factors: The “Art” of Finding a Fair Price

Not everything that matters can be put into a spreadsheet. A “fair price” also depends on the company’s Moat—its competitive advantage.

1. Brand Power

What is the “fair price” for a company that can raise prices by 10% every year and customers will still stay? Companies like Apple, Ferrari, or Coca-Cola have “Brand Moats.” This allows them to trade at a premium (a higher P/E) because their earnings are more predictable and “safe.”

2. The Network Effect

Some companies become more valuable as more people use them. Think of Meta (Facebook/Instagram) or Visa. If everyone is on the network, it’s almost impossible for a competitor to steal them away. This “switching cost” justifies a higher fair price.

3. Management Quality

Is the CEO a visionary who allocates capital wisely, or are they wasting money on “vanity projects”? A great management team can take a mediocre business and make it valuable, while a poor team can destroy a “fair price” overnight.

Common Valuation Traps: When “Cheap” is Actually a Disaster

Beginners often fall into “Value Traps.” A value trap is a stock that looks cheap based on the numbers but is actually headed for zero.

-

The Dying Industry: A company might have a P/E of $4, but if it sells a product that is becoming obsolete (like DVD rentals in 2010), that low price is justified. The “fair price” is actually lower than the market price.

-

The Debt Bomb: A company might look profitable, but if it has billions in high-interest debt coming due, the equity (the stock) might be worthless.

-

One-Time Gains: Sometimes a company sells a factory or an office building, which makes their “earnings” look huge for one quarter. This artificially lowers the P/E ratio. Always look for Normalized Earnings.

Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH): Does a Fair Price Even Matter?

There is a school of thought called the Efficient Market Hypothesis. It argues that all known information is already reflected in a stock’s price. Therefore, the “market price” is the “fair price” at any given second.

While this makes sense in theory, history proves it wrong. If the market were perfectly efficient, bubbles (like the 1999 Dot-Com bubble) and crashes (like 2008 or 2020) wouldn’t happen. The market is efficient most of the time, but it is inefficient enough of the time for disciplined investors to make a fortune.

How to Calculate Fair Price for Different Sectors

You cannot use the same “yardstick” for every industry.

-

Banking/Insurance: Focus on P/B (Price-to-Book) and ROE (Return on Equity). These companies are essentially piles of money, so their asset value matters most.

-

Tech/Software: Focus on Price-to-Sales (P/S) and Retention Rates. Since they have high growth and low physical assets, revenue and customer loyalty are the key drivers.

-

Real Estate (REITs): Use FFO (Funds From Operations) instead of net income. Standard accounting doesn’t work well for buildings that “depreciate” on paper but increase in value in real life.

-

Utility Companies: Focus on Dividend Yield and Payout Ratios. These are “income plays,” so the safety of the dividend is the primary driver of the fair price.

The Fair Price is a Range, Not a Point

Is there a fair price for a stock? Yes. But it is not a single, unchanging number like the price of a gallon of milk. Instead, it is a range of values based on probabilities.

As an investor, your goal is to:

-

Study the company’s fundamentals.

-

Calculate a conservative estimate of its intrinsic value.

-

Apply a generous Margin of Safety.

-

Wait for the market’s emotions to drive the price below your target.

When you buy a stock for $60 that you believe is worth $100, you aren’t gambling. You are engaging in a calculated business transaction. The market may not recognize the “fair price” today or tomorrow, but over the long run, the price always eventually meets the value.